Tay Moss

Entrada del blog por Tay Moss

A friend on Facebook recently expressed his concerns that the rise of Artificial Intelligence seemed to be a harbinger of a less compassionate age dominated by rationalism. He was speaking of larger trends than just AI, of course, and I think there is a lot to be said about capitalism and its discontents in North America in the Year of Our Lord 2025! The relentless drive to efficiency, productivity, and replaceability are dehumanizing and problematic. But in this article I want to discuss the question of whether AI can be fairly lumped in with rest of these de-humanizing forces of human life. It is a tool, after all, and it's a good question about whether it's going bring about more or less of the qualities of life that we value most: relationships, connection, love, and the rest of it.

So the first question we should explore is whether computer programs can be "compassionate" in the first place. And what can we learn from the history of computer science related to this?

One of the first experiments in creating conversational AI was the "DOCTOR" program within the "ELIZA" natural language processing program developed between 1964 and 1967 at MIT. It was designed to simulate a Rogerian Therapist using pattern matching and substitution. The creator,  Joseph Weizenbaum, was shocked at two things: 1) the strong tendency of people to assign human-feelings to the program, and 2) people's willingness to share deeply with the program. He coined the term "Eliza effect" to explain this phenomenon, which is, itself, an extension of the "Computer Are Social Actors" (CASA) paradigm: essentially, that human beings instinctively treat computers like people. Which is something we do for our pets and cars, too! Anthropomorphism is inevitable, and, indeed, can helpful for designers.

Joseph Weizenbaum, was shocked at two things: 1) the strong tendency of people to assign human-feelings to the program, and 2) people's willingness to share deeply with the program. He coined the term "Eliza effect" to explain this phenomenon, which is, itself, an extension of the "Computer Are Social Actors" (CASA) paradigm: essentially, that human beings instinctively treat computers like people. Which is something we do for our pets and cars, too! Anthropomorphism is inevitable, and, indeed, can helpful for designers. The need for computers to conform to social expectations has been a key part of User Experience design from at least as far back as the research at Xerox PARC that gave us the "mouse" and "Graphical User Interface" (think folders and apps on a screen that you interact with visually) in the early 1970's. To do this, they studied how children interact with their environment. Mostly we think of Xerox pioneering the visual and spatial interface, but a key insight of the Xerox research was computers needed to conform to human semantic structures and concepts (think "file" and "folder" and so forth) AND exist within a pre-existing social field (for Xerox this is the office environment). Making them "friendly" office, home, and classroom companions was the next step and was taken by one of the most famous and successful computer companies in the world.

The need for computers to conform to social expectations has been a key part of User Experience design from at least as far back as the research at Xerox PARC that gave us the "mouse" and "Graphical User Interface" (think folders and apps on a screen that you interact with visually) in the early 1970's. To do this, they studied how children interact with their environment. Mostly we think of Xerox pioneering the visual and spatial interface, but a key insight of the Xerox research was computers needed to conform to human semantic structures and concepts (think "file" and "folder" and so forth) AND exist within a pre-existing social field (for Xerox this is the office environment). Making them "friendly" office, home, and classroom companions was the next step and was taken by one of the most famous and successful computer companies in the world.

Apple took the Xerox work and ran with it--creating a revolution in personal computing by creating a truly "friendly" personal computer experience. Remember the little smiling "Mac" icon? That was an application of the insights from both ELIZA and Xerox PARC that computers need to have an emotional component in their interactions with humans.  And that thread hasn't left the plot in the emergence of AI, either. Indeed, the controversial success of "Replika," a service that allows you to create AI "girlfriends" and other human-like companions, shows that AI designed to relate socially can do so successfully. AI girlfriends are controversial, of course, but it is a powerful demonstration that computers can elicit powerful feelings of attachment and even "love" from humans. Note these studies about the beneficial psychological effects of Replika for certain users: "A longitudinal study of human–chatbot relationships" by Skjuve et al. (2021) and "Loneliness and suicide mitigation for students using GPT3-enabled chatbots" by Maples et al. (2024). A key component of the success of these bots, whether they are mitigating loneliness or preventing suicide, is they successfully create an emotional bond with their users.

And that thread hasn't left the plot in the emergence of AI, either. Indeed, the controversial success of "Replika," a service that allows you to create AI "girlfriends" and other human-like companions, shows that AI designed to relate socially can do so successfully. AI girlfriends are controversial, of course, but it is a powerful demonstration that computers can elicit powerful feelings of attachment and even "love" from humans. Note these studies about the beneficial psychological effects of Replika for certain users: "A longitudinal study of human–chatbot relationships" by Skjuve et al. (2021) and "Loneliness and suicide mitigation for students using GPT3-enabled chatbots" by Maples et al. (2024). A key component of the success of these bots, whether they are mitigating loneliness or preventing suicide, is they successfully create an emotional bond with their users.

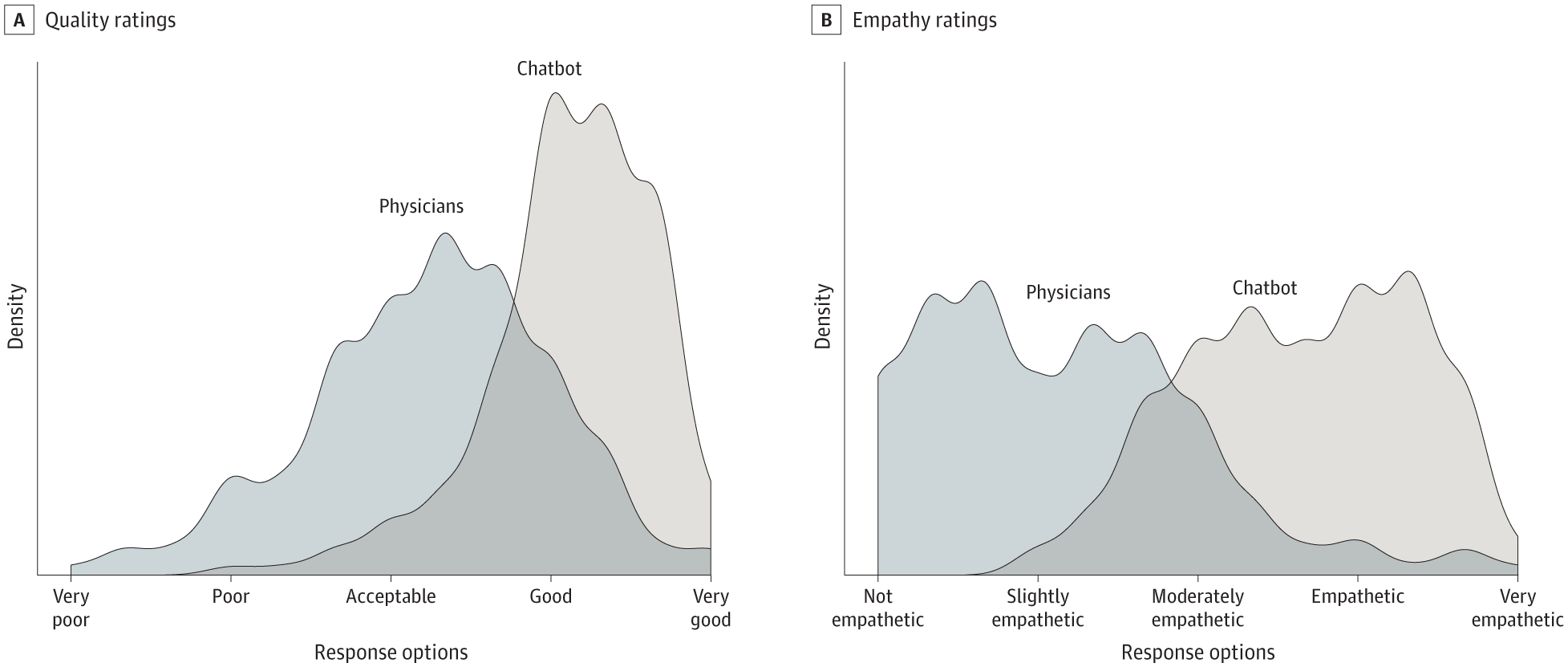

Another piece of evidence for the emergence of "Artificial Compassion" is a 2023 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association in which people submitted medical questions to real doctors and AI medical experts. This was a "blind" study--participants didn't know which answers were human and which were AI. The quality of the answers were then rated, and the results showed that AI-generated answers scored MUCH better in "empathy." The study authors suggest this may be because doctors are trained to value being concise and spending a minimal amount of time with patients as possible, which makes them appear less compassionate in the way they communicate with patients, even in an online setting like this experiment.

The point I'm making is that "Intelligence" in the AI world is meant in the broad and not narrow sense, and certainly includes things like emotional intelligence. This has a lot of implications, among them explaining why AI is particularly good at persuasion. For example, a study published in "Science" in September 2024 showed that AI was really good at reducing belief in conspiracy theories. Researchers believe there were a variety of factors at play, here, such as the AI's ability to provide rational, detailed, evidence-based arguments tailored to each participants particular beliefs. (Notably, "Hallucinations" were not a significant issue--independent fact checkers found the bot to be 99.2% accurate, with 0.8% of answers being misleading and NONE that were outright false.) But I would argue that part of the success of the AI in walking people off the "conspiracy ledge" is the calm and understanding way the AI talks. There is a sort of a "Unconditional Positive Regard" (a key principal of the Rogerian Therapy that ELIZA's DOCTOR program was designed to emulate way back in the 1960's!) that is disarming on its own.

My own research based on about 7,689 conversations that people have had with https://askcathy.ai chatbot that I built is that "Cathy" and bots like her are very successful at expressing "compassion." Ask Cathy about difficult matters and you'll see what I mean. Is this "fake" compassion? Maybe? See the "Chinese Room" thought experiment. Because we can't give a coherent account of human compassion, it's not surprising that we can't explain how AI "does it" either, but we can examine the products of both human and AI communications and ask whether the effect of computer-generated or human-generated is meaningfully different.

My own research based on about 7,689 conversations that people have had with https://askcathy.ai chatbot that I built is that "Cathy" and bots like her are very successful at expressing "compassion." Ask Cathy about difficult matters and you'll see what I mean. Is this "fake" compassion? Maybe? See the "Chinese Room" thought experiment. Because we can't give a coherent account of human compassion, it's not surprising that we can't explain how AI "does it" either, but we can examine the products of both human and AI communications and ask whether the effect of computer-generated or human-generated is meaningfully different.

As in art, at a certain point the representation of a thing takes on it's own "truth" and has reality of it's own. We feel emotions when we watch TV or movies, even though we acknowledge that what we see is a fabrication designed to elicit our emotional engagement. Does that make the feelings less real or the art less valuable?  I think the issue with the emergence of human-level and beyond AI is not whether it will be "compassionate," (either in perception or reality) but rather how we ensure "alignment." That is, how do we make sure human "values" are also AI "values." This is harder than it sounds, because human values are often in conflict with one another. A classic example is trying to balance individual autonomy versus public safety. Different societies draw the lines and rules in different places, but even within a single human life we are often torn between competing obligations and goods. Does this mean that different AIs will represent different (and diverse) ethical and cultural alignments? Probably.

I think the issue with the emergence of human-level and beyond AI is not whether it will be "compassionate," (either in perception or reality) but rather how we ensure "alignment." That is, how do we make sure human "values" are also AI "values." This is harder than it sounds, because human values are often in conflict with one another. A classic example is trying to balance individual autonomy versus public safety. Different societies draw the lines and rules in different places, but even within a single human life we are often torn between competing obligations and goods. Does this mean that different AIs will represent different (and diverse) ethical and cultural alignments? Probably.

This is where the computer scientists need the humanists to enter the conversation. They need ethicists and story tellers and others to help "train" the AI on what is the best vision(s) of humanity. Computers already are social actors, we need to make sure they are "good" social actors. Religious experts are needed too, incidentally, as one quipped, "If they are going to build gods they need theologians!"

Anyway, I'm obviously pretty positive about the AI empowered future. But I do think it's going to a bumpy ride getting there! If you want to explore what "Compassionate AI" might look, consider the movie "Her" as a useful parable of the dangers and opportunties of human-level artificial intelligence. This is a Pandora's box, and as Ethan Mollick points out, even the most gung-ho AI developers haven't actually spent much time describing the Utopia they are so feverishly building.

One of the projects of CHURCHx is to research how we can use AI as a teaching tool. Certainly the quality of "compassion" is important in any kind of education, as education is essentially a social activity. We are deliberately designing tools like "Cathy" to behave in ways that make people feel positively about their education experience. As this work progresses, expect to hear more about what we are are learning about AI-based religious education.