CHURCHx

Blog del sitio

From Passive to Profound: How Fink’s Model Enhances Religious Education

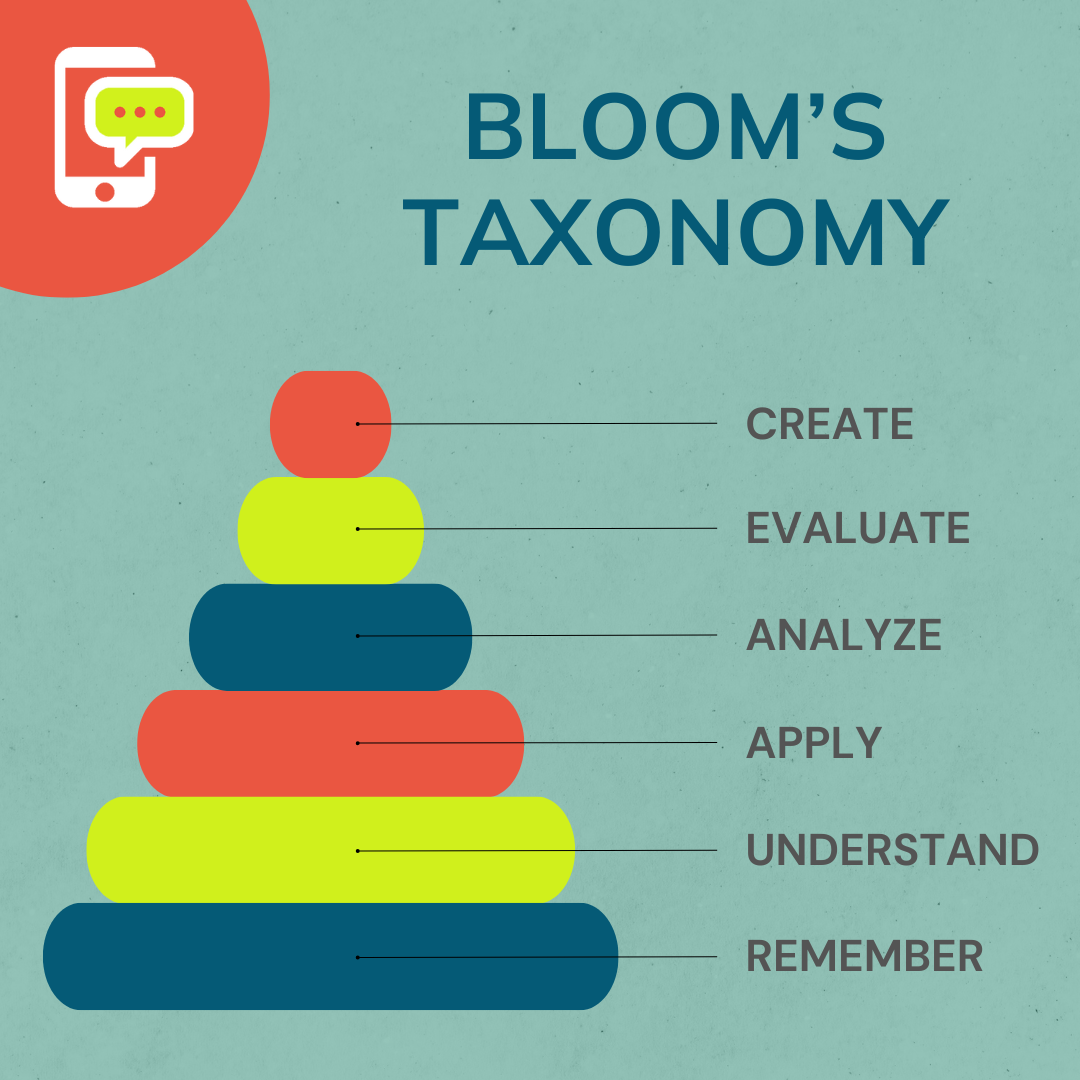

As religious educators, we aim to create learning experiences that have a lasting impact on our communities, fostering both intellectual and spiritual growth. A few weeks ago I wrote about Bloom's Taxonomy in this blog. While Bloom's Taxonomy has long been a valuable tool for understanding cognitive learning, L. Dee Fink's paradigm of "Significant Learning" offers a fresh and holistic approach that can revolutionize how we design and facilitate learning in religious settings. This article explores Fink's framework, contrasting it with Bloom's Taxonomy, and provides concrete examples of its application in various religious education contexts. In doing so, we will see how Fink's model shifts the focus from a content-centered approach to a learning-centered approach, asking not just "what" will students learn, but "how" and "why".

Bloom's Taxonomy: A Foundation for Understanding Learning

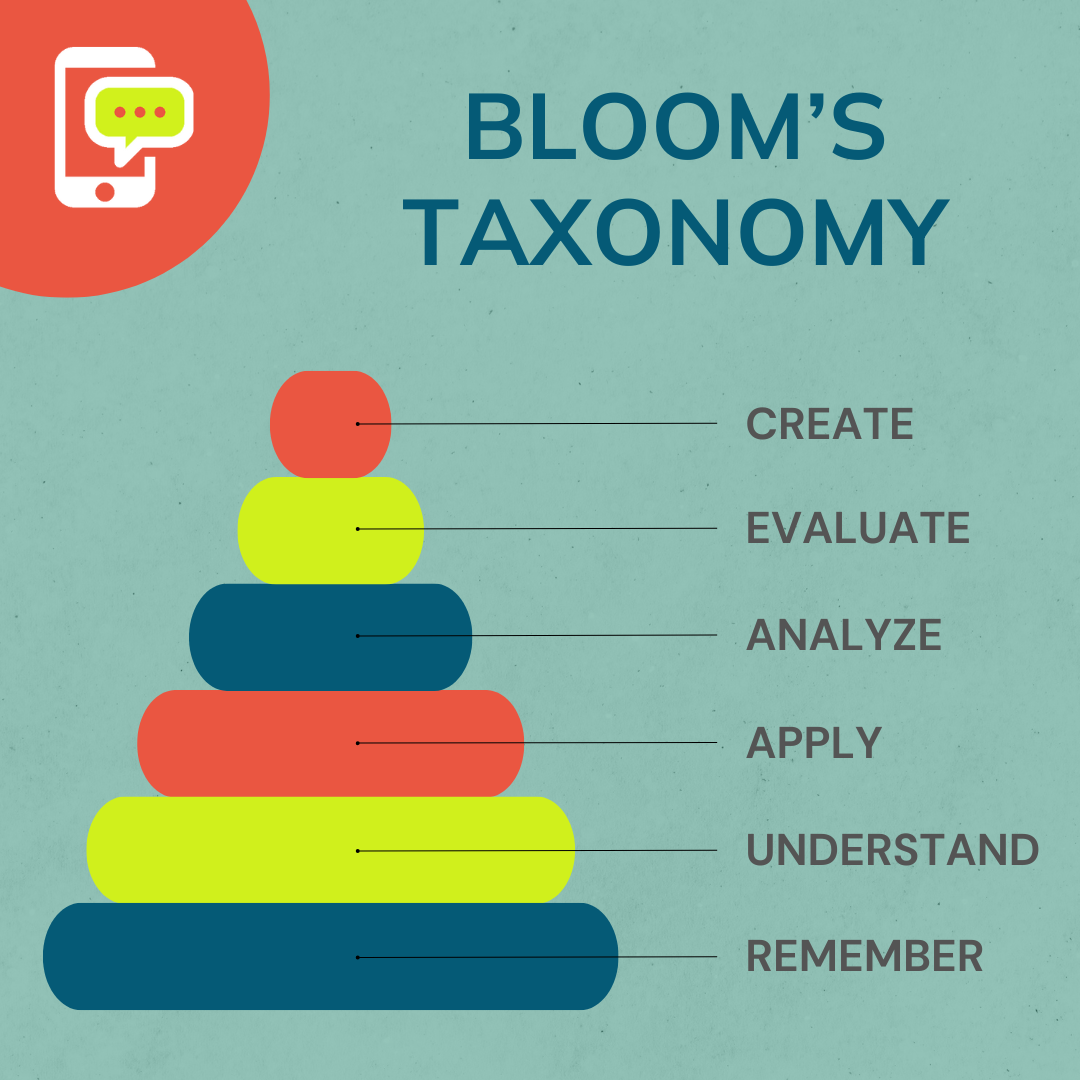

Before delving into Fink's work, let's briefly revisit Bloom's Taxonomy. Developed in 1956 by a group of educators led by Benjamin Bloom, this hierarchical model classifies learning objectives into six cognitive levels: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating . This framework has been instrumental in helping educators structure learning experiences and assessments that progressively challenge students to engage with information in increasingly complex ways.

Before delving into Fink's work, let's briefly revisit Bloom's Taxonomy. Developed in 1956 by a group of educators led by Benjamin Bloom, this hierarchical model classifies learning objectives into six cognitive levels: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating . This framework has been instrumental in helping educators structure learning experiences and assessments that progressively challenge students to engage with information in increasingly complex ways.

For instance, in a Bible study setting, Bloom's Taxonomy can guide us to design activities that move beyond simple recall (remembering) to encourage deeper understanding (e.g., interpreting parables), application (e.g., relating biblical principles to daily life), analysis (e.g., comparing different theological interpretations), evaluation (e.g., assessing the validity of different arguments), and ultimately, creation (e.g., developing a personal theology or action plan based on biblical teachings) .

Fink's Significant Learning: Expanding the Horizons of Learning

Fink's Significant Learning: Expanding the Horizons of Learning

Building upon Bloom's foundation, L. Dee Fink introduced his taxonomy of "Significant Learning" in 2003. An education consultant, Fink was struck by the passion teachers feel that go well beyond the immediate goals of most classes and into life-changing learning. A typical question he would ask is "In 10 years, what do you want to be different about students because they took your class?" Teachers would talk about inspiring a love of learning in the topic and other more "significant" changes. L. Dee Fink defined "significant learning" as a transformative educational experience that goes beyond simply acquiring information. In his book Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses (2003), Fink outlined a Taxonomy of Significant Learning, which emphasizes learning that leads to lasting change in the learner’s life—intellectually, personally, and socially. Fink's model recognizes that truly transformative learning is more than just remembering facts and figures; it's about making connections and changing perspectives. This model goes beyond the cognitive domain to encompass the affective and metacognitive dimensions of learning as well .

He identifies six interactive categories of significant learning:

| Category of Learning | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Foundational Knowledge | Understanding and remembering information and ideas |

| Application | Learning how to do something new: skills, critical thinking, creative thinking, practical thinking, and managing projects |

| Integration | Connecting information, ideas, perspectives, people, or realms of life |

| Human Dimension | Learning about oneself and others |

| Caring | Developing new feelings, interests, and values |

| Learning How to Learn | Becoming a better student, inquiring about a subject, becoming a self-directed learner |

Unlike Bloom's hierarchical structure, Fink's categories are interconnected and non-linear. This means that learning in one category can facilitate and enhance learning in others . For example, as students learn more about how a topic applies to their lives (Human Dimension), they may also develop a deeper appreciation for the subject itself (Caring) . It is important to note that Fink believes that for significant learning to occur, all six dimensions need to be addressed in the design of a course. However, many who apply Fink's model in practice focus on three or four areas.

Applying Fink's Significant Learning in Religious Settings

Fink's framework provides a powerful lens for designing engaging and impactful learning experiences in religious contexts. Let's explore some concrete examples:

1. Seminary Classes:

Imagine a seminary course on the Book of Romans. To foster Foundational Knowledge, students could engage in a "jigsaw" activity where they each become experts on a specific chapter and then teach their peers. To encourage Application, students could write a modern-day letter to a specific community, applying Paul's message to their context. For Integration, students could explore how Romans has been interpreted throughout history and its influence on art, literature, and social movements. The Human Dimension could be addressed through journaling and small group discussions where students reflect on how Paul's teachings challenge their own beliefs and values. Caring could be fostered by inviting guest speakers who embody the principles of Romans in their lives, inspiring students to connect with the material on an emotional level.

2. Church Bible Studies:

In a Bible study on the Parable of the Good Samaritan, Foundational Knowledge could be established through a close reading of the text, exploring its historical and cultural context. Application could involve a group discussion where participants share personal experiences of encountering "neighbors" in need and how they responded. To encourage Integration, the group could discuss how the parable connects to contemporary issues like immigration, poverty, and racial justice. The Human Dimension could be explored through a guided meditation where participants reflect on their own biases and prejudices. Caring could be fostered by partnering with a local charity to put the message of the parable into action.

3. Youth Ministry Programs:

A youth group studying the life of Jesus could build Foundational Knowledge through interactive games and quizzes. Application could involve a role-playing activity where youth act out scenes from Jesus' life, exploring how they would respond in similar situations. Integration could be encouraged by having youth create artwork or music that expresses their understanding of Jesus' teachings. The Human Dimension could be addressed through small group discussions where youth share their personal struggles and how they find strength in their faith. Caring could be fostered by organizing a service project where youth put their faith into action by helping those in need.

Learning How to Learn in Religious Education

Across all these settings, Learning How to Learn is crucial. This involves equipping individuals with the tools and strategies for ongoing spiritual growth and engagement with their faith. This could include teaching them how to study scripture independently, engage in different forms of prayer and meditation, and cultivate a habit of self-reflection. It also involves encouraging them to ask questions, seek out diverse perspectives, and be open to new understandings of their faith. The goal is not only to equip them to be lifelong learners, but to inspire passion and a sense of their own capabilies to explore independently.

Across all these settings, Learning How to Learn is crucial. This involves equipping individuals with the tools and strategies for ongoing spiritual growth and engagement with their faith. This could include teaching them how to study scripture independently, engage in different forms of prayer and meditation, and cultivate a habit of self-reflection. It also involves encouraging them to ask questions, seek out diverse perspectives, and be open to new understandings of their faith. The goal is not only to equip them to be lifelong learners, but to inspire passion and a sense of their own capabilies to explore independently.

Challenges and Opportunities for Religious Educators

Religious educators face unique challenges in designing learning experiences. They must balance the need for relevance, connecting ancient texts and traditions to the lives of contemporary learners, with faithfulness to the core tenets of their faith . They must also navigate the complexities of fostering emotional and spiritual intelligence, helping individuals develop self-awareness, empathy, and a capacity for moral reasoning . In today's world, where distractions abound and attention spans are shrinking, motivating and engaging students in religious settings can be particularly challenging .

However, these challenges also present opportunities. By embracing innovative teaching methods, incorporating technology and multimedia, and fostering inclusive learning environments, religious educators can create transformative experiences that inspire a lifelong love of learning and a deeper connection to faith.

Bloom's and Fink's Taxonomies: A Comparison

To further clarify the distinct contributions of each framework, the following table summarizes the key differences between Bloom's Taxonomy and Fink's Significant Learning:

| Feature | Bloom's Taxonomy | Fink's Significant Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Hierarchical | Interactive |

| Focus | Cognitive | Holistic (cognitive, affective, and metacognitive) |

| Application | Primarily for assessing cognitive skills | For designing significant learning experiences that foster lasting change |

Conclusion: Embracing Significant Learning for Transformative Religious Education

Fink's paradigm of Significant Learning offers a valuable framework for religious educators seeking to create transformative learning experiences. By intentionally incorporating all six categories of learning, we can design programs that not only impart knowledge but also foster personal growth, inspire a love of learning, and equip individuals to live out their faith in meaningful ways. Fink's emphasis on personal growth, affective learning, and metacognition directly addresses the challenges of fostering spiritual development, promoting meaningful engagement with religious texts, and equipping individuals for ministry in a diverse and changing world. By moving beyond a purely cognitive approach, we can create learning environments that nurture the whole person, cultivate a deeper connection to faith, and empower individuals to make a positive impact on the world.

A friend on Facebook recently expressed his concerns that the rise of Artificial Intelligence seemed to be a harbinger of a less compassionate age dominated by rationalism. He was speaking of larger trends than just AI, of course, and I think there is a lot to be said about capitalism and its discontents in North America in the Year of Our Lord 2025! The relentless drive to efficiency, productivity, and replaceability are dehumanizing and problematic. But in this article I want to discuss the question of whether AI can be fairly lumped in with rest of these de-humanizing forces of human life. It is a tool, after all, and it's a good question about whether it's going bring about more or less of the qualities of life that we value most: relationships, connection, love, and the rest of it.

So the first question we should explore is whether computer programs can be "compassionate" in the first place. And what can we learn from the history of computer science related to this?

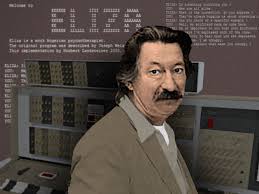

One of the first experiments in creating conversational AI was the "DOCTOR" program within the "ELIZA" natural language processing program developed between 1964 and 1967 at MIT. It was designed to simulate a Rogerian Therapist using pattern matching and substitution. The creator,  Joseph Weizenbaum, was shocked at two things: 1) the strong tendency of people to assign human-feelings to the program, and 2) people's willingness to share deeply with the program. He coined the term "Eliza effect" to explain this phenomenon, which is, itself, an extension of the "Computer Are Social Actors" (CASA) paradigm: essentially, that human beings instinctively treat computers like people. Which is something we do for our pets and cars, too! Anthropomorphism is inevitable, and, indeed, can helpful for designers.

Joseph Weizenbaum, was shocked at two things: 1) the strong tendency of people to assign human-feelings to the program, and 2) people's willingness to share deeply with the program. He coined the term "Eliza effect" to explain this phenomenon, which is, itself, an extension of the "Computer Are Social Actors" (CASA) paradigm: essentially, that human beings instinctively treat computers like people. Which is something we do for our pets and cars, too! Anthropomorphism is inevitable, and, indeed, can helpful for designers. The need for computers to conform to social expectations has been a key part of User Experience design from at least as far back as the research at Xerox PARC that gave us the "mouse" and "Graphical User Interface" (think folders and apps on a screen that you interact with visually) in the early 1970's. To do this, they studied how children interact with their environment. Mostly we think of Xerox pioneering the visual and spatial interface, but a key insight of the Xerox research was computers needed to conform to human semantic structures and concepts (think "file" and "folder" and so forth) AND exist within a pre-existing social field (for Xerox this is the office environment). Making them "friendly" office, home, and classroom companions was the next step and was taken by one of the most famous and successful computer companies in the world.

The need for computers to conform to social expectations has been a key part of User Experience design from at least as far back as the research at Xerox PARC that gave us the "mouse" and "Graphical User Interface" (think folders and apps on a screen that you interact with visually) in the early 1970's. To do this, they studied how children interact with their environment. Mostly we think of Xerox pioneering the visual and spatial interface, but a key insight of the Xerox research was computers needed to conform to human semantic structures and concepts (think "file" and "folder" and so forth) AND exist within a pre-existing social field (for Xerox this is the office environment). Making them "friendly" office, home, and classroom companions was the next step and was taken by one of the most famous and successful computer companies in the world.

Apple took the Xerox work and ran with it--creating a revolution in personal computing by creating a truly "friendly" personal computer experience. Remember the little smiling "Mac" icon? That was an application of the insights from both ELIZA and Xerox PARC that computers need to have an emotional component in their interactions with humans.  And that thread hasn't left the plot in the emergence of AI, either. Indeed, the controversial success of "Replika," a service that allows you to create AI "girlfriends" and other human-like companions, shows that AI designed to relate socially can do so successfully. AI girlfriends are controversial, of course, but it is a powerful demonstration that computers can elicit powerful feelings of attachment and even "love" from humans. Note these studies about the beneficial psychological effects of Replika for certain users: "A longitudinal study of human–chatbot relationships" by Skjuve et al. (2021) and "Loneliness and suicide mitigation for students using GPT3-enabled chatbots" by Maples et al. (2024). A key component of the success of these bots, whether they are mitigating loneliness or preventing suicide, is they successfully create an emotional bond with their users.

And that thread hasn't left the plot in the emergence of AI, either. Indeed, the controversial success of "Replika," a service that allows you to create AI "girlfriends" and other human-like companions, shows that AI designed to relate socially can do so successfully. AI girlfriends are controversial, of course, but it is a powerful demonstration that computers can elicit powerful feelings of attachment and even "love" from humans. Note these studies about the beneficial psychological effects of Replika for certain users: "A longitudinal study of human–chatbot relationships" by Skjuve et al. (2021) and "Loneliness and suicide mitigation for students using GPT3-enabled chatbots" by Maples et al. (2024). A key component of the success of these bots, whether they are mitigating loneliness or preventing suicide, is they successfully create an emotional bond with their users.

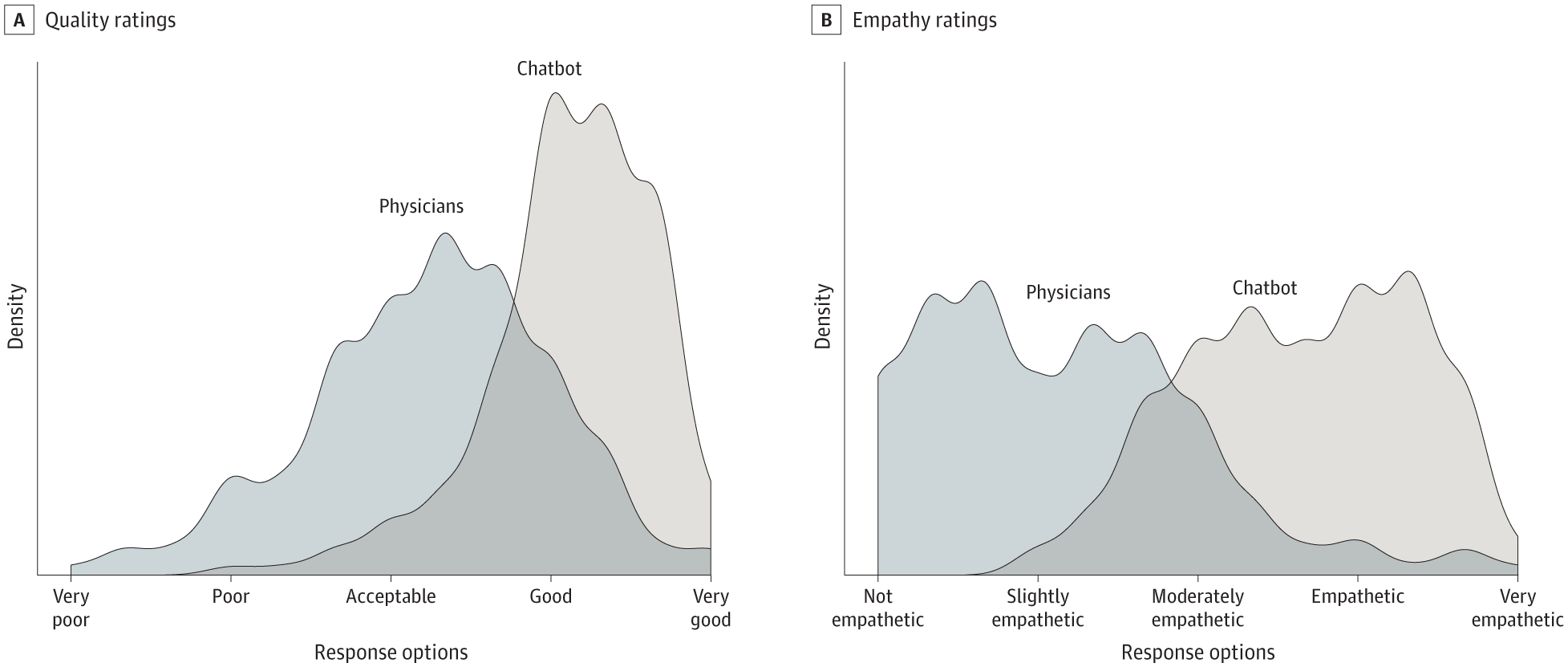

Another piece of evidence for the emergence of "Artificial Compassion" is a 2023 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association in which people submitted medical questions to real doctors and AI medical experts. This was a "blind" study--participants didn't know which answers were human and which were AI. The quality of the answers were then rated, and the results showed that AI-generated answers scored MUCH better in "empathy." The study authors suggest this may be because doctors are trained to value being concise and spending a minimal amount of time with patients as possible, which makes them appear less compassionate in the way they communicate with patients, even in an online setting like this experiment.

The point I'm making is that "Intelligence" in the AI world is meant in the broad and not narrow sense, and certainly includes things like emotional intelligence. This has a lot of implications, among them explaining why AI is particularly good at persuasion. For example, a study published in "Science" in September 2024 showed that AI was really good at reducing belief in conspiracy theories. Researchers believe there were a variety of factors at play, here, such as the AI's ability to provide rational, detailed, evidence-based arguments tailored to each participants particular beliefs. (Notably, "Hallucinations" were not a significant issue--independent fact checkers found the bot to be 99.2% accurate, with 0.8% of answers being misleading and NONE that were outright false.) But I would argue that part of the success of the AI in walking people off the "conspiracy ledge" is the calm and understanding way the AI talks. There is a sort of a "Unconditional Positive Regard" (a key principal of the Rogerian Therapy that ELIZA's DOCTOR program was designed to emulate way back in the 1960's!) that is disarming on its own.

My own research based on about 7,689 conversations that people have had with https://askcathy.ai chatbot that I built is that "Cathy" and bots like her are very successful at expressing "compassion." Ask Cathy about difficult matters and you'll see what I mean. Is this "fake" compassion? Maybe? See the "Chinese Room" thought experiment. Because we can't give a coherent account of human compassion, it's not surprising that we can't explain how AI "does it" either, but we can examine the products of both human and AI communications and ask whether the effect of computer-generated or human-generated is meaningfully different.

My own research based on about 7,689 conversations that people have had with https://askcathy.ai chatbot that I built is that "Cathy" and bots like her are very successful at expressing "compassion." Ask Cathy about difficult matters and you'll see what I mean. Is this "fake" compassion? Maybe? See the "Chinese Room" thought experiment. Because we can't give a coherent account of human compassion, it's not surprising that we can't explain how AI "does it" either, but we can examine the products of both human and AI communications and ask whether the effect of computer-generated or human-generated is meaningfully different.

As in art, at a certain point the representation of a thing takes on it's own "truth" and has reality of it's own. We feel emotions when we watch TV or movies, even though we acknowledge that what we see is a fabrication designed to elicit our emotional engagement. Does that make the feelings less real or the art less valuable?  I think the issue with the emergence of human-level and beyond AI is not whether it will be "compassionate," (either in perception or reality) but rather how we ensure "alignment." That is, how do we make sure human "values" are also AI "values." This is harder than it sounds, because human values are often in conflict with one another. A classic example is trying to balance individual autonomy versus public safety. Different societies draw the lines and rules in different places, but even within a single human life we are often torn between competing obligations and goods. Does this mean that different AIs will represent different (and diverse) ethical and cultural alignments? Probably.

I think the issue with the emergence of human-level and beyond AI is not whether it will be "compassionate," (either in perception or reality) but rather how we ensure "alignment." That is, how do we make sure human "values" are also AI "values." This is harder than it sounds, because human values are often in conflict with one another. A classic example is trying to balance individual autonomy versus public safety. Different societies draw the lines and rules in different places, but even within a single human life we are often torn between competing obligations and goods. Does this mean that different AIs will represent different (and diverse) ethical and cultural alignments? Probably.

This is where the computer scientists need the humanists to enter the conversation. They need ethicists and story tellers and others to help "train" the AI on what is the best vision(s) of humanity. Computers already are social actors, we need to make sure they are "good" social actors. Religious experts are needed too, incidentally, as one quipped, "If they are going to build gods they need theologians!"

Anyway, I'm obviously pretty positive about the AI empowered future. But I do think it's going to a bumpy ride getting there! If you want to explore what "Compassionate AI" might look, consider the movie "Her" as a useful parable of the dangers and opportunties of human-level artificial intelligence. This is a Pandora's box, and as Ethan Mollick points out, even the most gung-ho AI developers haven't actually spent much time describing the Utopia they are so feverishly building.

One of the projects of CHURCHx is to research how we can use AI as a teaching tool. Certainly the quality of "compassion" is important in any kind of education, as education is essentially a social activity. We are deliberately designing tools like "Cathy" to behave in ways that make people feel positively about their education experience. As this work progresses, expect to hear more about what we are are learning about AI-based religious education.

In the mid-20th century, educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom and his

colleagues sought to develop a systematic approach to how educators could

categorize and promote learning objectives. Their framework, now known as Bloom’s

Taxonomy, offers a layered structure for learning that moves from basic

knowledge acquisition to higher-order thinking skills. Bloom’s original

taxonomy included six cognitive categories arranged hierarchically: Knowledge,

Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. In 2001,

it was revised to more active verbs: Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate,

and Create. Each element builds on the previous one, providing a useful

framework for educators designing both synchronous and asynchronous courses.

For those in theological

education, Bloom’s structure can serve as a valuable tool to deepen not

only cognitive engagement but also spiritual formation.

[RE1]

Applying the insights gained from Bloom’s Taxonomy can

make your programs more effective at wholistically engaging people whether in

the church or on CHURCHx.

In the mid-20th century, educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom and his

colleagues sought to develop a systematic approach to how educators could

categorize and promote learning objectives. Their framework, now known as Bloom’s

Taxonomy, offers a layered structure for learning that moves from basic

knowledge acquisition to higher-order thinking skills. Bloom’s original

taxonomy included six cognitive categories arranged hierarchically: Knowledge,

Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. In 2001,

it was revised to more active verbs: Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate,

and Create. Each element builds on the previous one, providing a useful

framework for educators designing both synchronous and asynchronous courses.

For those in theological

education, Bloom’s structure can serve as a valuable tool to deepen not

only cognitive engagement but also spiritual formation.

[RE1]

Applying the insights gained from Bloom’s Taxonomy can

make your programs more effective at wholistically engaging people whether in

the church or on CHURCHx.

The Six Levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy in Theological Education

1. Remember:

This foundational level asks students to recall information accurately. For theological education, this could involve memorizing scripture, church creeds, or theological definitions.

- Example for Synchronous Learning: In a Zoom class, students participate in a quiz game like Kahoot! to test their recall of biblical texts.

- Example for Asynchronous Learning: An online course might feature flashcards or quizzes that allow students to practice key terms and concepts, such as defining the term “eschatology.”

2. Understand:

At this level, students move beyond memorization to comprehend the meaning of what they have learned. They should be able to summarize and interpret information.

- Example for Synchronous Learning: In a live discussion, a professor asks students to summarize the parable of the Prodigal Son and explain what it teaches about grace.

- Example for Asynchronous Learning: A Moodle forum asks students to post responses to questions about Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Cost of Discipleship,” encouraging them to explain concepts in their own words.

3. Apply:

Application requires learners to use knowledge in new situations. For theology students, this could mean applying scripture to real-world pastoral situations or ethical dilemmas.

- Example for Synchronous Learning: In a breakout group during a live class, students role-play how they would counsel someone using principles from Pauline theology.

- Example for Asynchronous Learning: A course module challenges students to write a short reflection on how they might apply the concept of agape love in a community outreach setting.

4. Analyze:

This stage requires students to break down complex information into components to understand relationships between them. Analysis encourages critical thinking and deeper engagement.

- Example for Synchronous Learning: In a real-time classroom debate, students analyze different theological perspectives on predestination, identifying key similarities and differences.

- Example for Asynchronous Learning: Students submit essays comparing the Synoptic Gospels, noting differences in the portrayal of Jesus and how each gospel serves its particular audience.

5. Evaluate:

Evaluation involves making judgments about the value of ideas, practices, or information. In theological education, this might mean assessing the strengths and weaknesses of theological arguments.

- Example for Synchronous Learning: In a classroom discussion, students evaluate whether Augustine’s doctrine of original sin is relevant to modern pastoral practice.

- Example for Asynchronous Learning: Using peer review tools, students critique one another’s sermon drafts, offering constructive feedback.

6. Create:

The highest level of Bloom’s taxonomy encourages students to synthesize ideas into new forms or frameworks. This is where theological students can innovate by contributing new ideas to ongoing theological conversations.

- Example for Synchronous Learning: Students collaborate on developing a liturgy for a new worship service, drawing from historical and contemporary sources.

- Example for Asynchronous Learning: A final course project invites students to design a teaching module or Bible study curriculum that reflects both theological rigor and cultural relevance.

Critiques of Bloom’s Taxonomy and Alternative Models

While Bloom’s Taxonomy is widely used, it has not escaped critique. One of the primary criticisms is that the taxonomy assumes a linear and hierarchical model of learning—where students must master lower levels before moving to higher ones. This can oversimplify the complexity of learning, especially in disciplines like theology where knowledge and application are often intertwined. For example, spiritual formation involves both reflection and practical action at every stage, not neatly fitting into a step-by-step cognitive hierarchy.

Alternative frameworks, such as Anderson and Krathwohl’s revision (which emphasizes the interrelatedness of knowledge types and cognitive processes) and Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning, stress the importance of emotional and relational learning. Fink’s model, in particular, focuses on integrating knowledge with self-reflection, which may be more aligned with theological education’s goals of personal transformation and community engagement.

Additionally, some educators prefer constructivist approaches, emphasizing learning as an active, student-centered process that does not follow a fixed sequence. This is especially relevant in asynchronous courses, where students engage at their own pace and in their own sequence, encountering knowledge in non-linear waysWhere to Learn More

For educators and theologians looking to explore Bloom’s Taxonomy further, the following resources are helpful starting points:

- For practical ideas about applying Bloom’s Taxonomy in online courses, visit resources like the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching.

- Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

By understanding and thoughtfully applying Bloom’s Taxonomy, theological educators can design courses that engage students deeply—both cognitively and spiritually—while remaining open to alternative models that enrich their pedagogy.

CHURCHx, as a platform, is much more versatile than most Learning Management Systems, and can therefore support multi-modal methodologies that hit multiple stages at once. This is consistent with our “constructivist” approach to learning, which emphasizes a learner-first approach with multiple ways to engage the same content. Many off-the-shelf learning systems seem to stop at the “remember” stage of learning—simply delivering content. CHURCHx is able to create rich opportunities for students to apply and create new knowledge that has emerged from their learning experience.

If you want to learn more about how to integrate Bloom’s Taxonomy into

your work, whether you teach in an institution or are a pastor of a church or do

adult formation in another way, we suggest the course “Learning Design for Discipleship” created by Dr. Natalie Wigg-Stevenson.

If you want to learn more about how to integrate Bloom’s Taxonomy into

your work, whether you teach in an institution or are a pastor of a church or do

adult formation in another way, we suggest the course “Learning Design for Discipleship” created by Dr. Natalie Wigg-Stevenson.

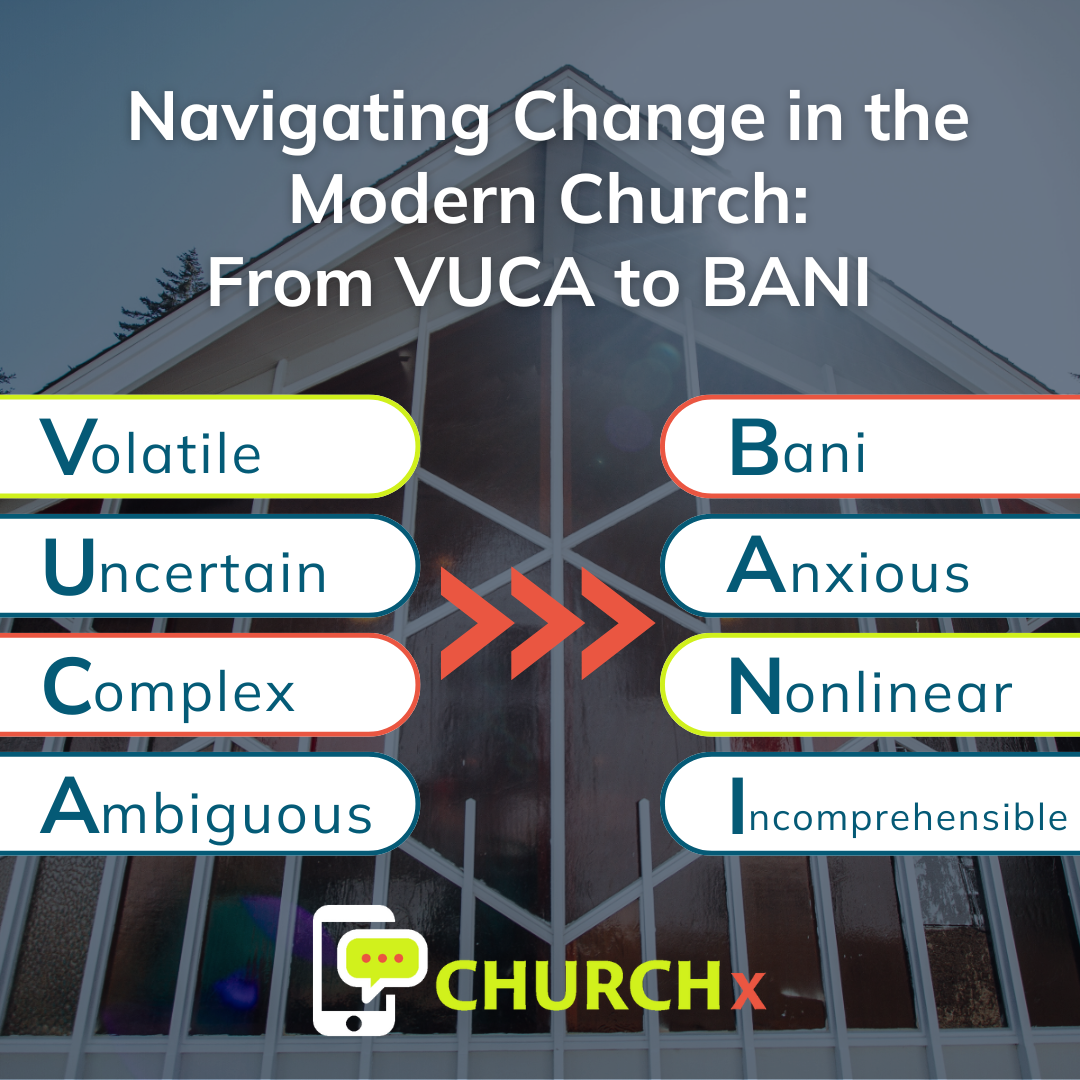

In this blog article I want to talk about how we characterize the current context of ministry. Tools like these frameworks help us to broaden our imagination and better cope with the challenges of ministry.

Introduction

The world of the church, particularly mainline denominations, has been experiencing unprecedented challenges and changes in recent years. To understand and respond to these shifts, it's crucial to examine the evolving frameworks used to describe our complex environment: from VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous) to BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, Incomprehensible). This essay will explore how these concepts apply to the church's current situation, with a focus on the impact of COVID-19 and the acceleration of existing trends. Finally, we'll discuss strategies for ministry in this new landscape.

VUCA: The Initial Framework

The concept of VUCA, originally popularized by the U.S. Army War College, has been used since the late 1980s to describe the post-Cold War world. In the context of the church, VUCA can be applied as follows:

- Volatile: Rapid changes in church attendance and engagement.

- Uncertain: Unclear future for traditional religious institutions.

- Complex: Intersecting social, cultural, and technological factors affecting faith communities.

- Ambiguous: Blurred lines between spiritual practices and secular alternatives.

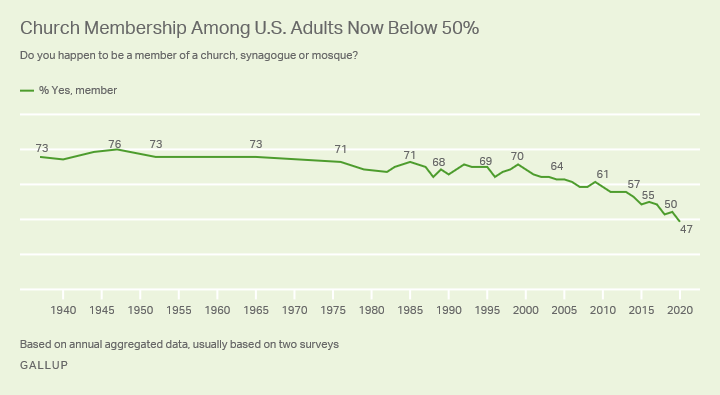

For years, mainline churches have grappled with these VUCA conditions, facing declining membership, shifting cultural values, and the challenge of remaining relevant in an increasingly secular society.

The Shift to BANI

As the pace of change accelerated, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it appeared that “VUCA wasn’t VUCA enough!” So, a new framework emerged: BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, Incomprehensible). This concept, introduced by Jamais Cascio in 2020, offers a more nuanced understanding of our current reality:

- Brittle: Systems and institutions that appear strong but are vulnerable to sudden collapse.

- Anxious: Pervasive sense of fear and dread about the future.

- Nonlinear: Disproportionate, unpredictable cause-and-effect relationships.

- Incomprehensible: Situations that defy straightforward analysis or solution.

BANI and the Church in the Post-COVID Era

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a catalyst, intensifying the challenges already faced by mainline churches and accelerating their decline. The BANI framework helps us understand this new landscape: - Brittle: Many churches that relied heavily on in-person gatherings found themselves suddenly unable to function when lockdowns were imposed. This revealed the brittleness of traditional church models.

- Anxious: The pandemic heightened existing anxieties about the future of organized religion, with concerns about health, financial stability, and community cohesion intensifying the sense of unease.

- Nonlinear: Small changes in health policies or social norms led to dramatic shifts in church attendance and engagement. The rapid adoption of online services, for instance, had far-reaching and often unexpected consequences for congregations. For example, many congregations found themselves with a group of online followers who would be exclusively online participants in their community life. Another consequence was “virtual church shopping” in which congregants were diverse worship styles previously only available through in-person attendance. Exposing congregation members to diverse worship styles had the knock-on-affect of them suggesting improvements or changes to their home congregations.

- Incomprehensible: The long-term impacts of the pandemic on religious practice and spirituality remain difficult to predict or fully understand, leaving many church leaders feeling overwhelmed and uncertain about how to proceed.

Applying BANI Principles to Ministry

Applying BANI Principles to Ministry

Understanding the BANI framework can help church leaders develop more effective strategies for ministry in this challenging environment. Here are some approaches to consider:

1. Embracing Flexibility (Countering Brittleness):

- Develop hybrid models of worship that combine in-person and online elements. Examples:

- Interacting via chat with YouTube/Facebook audience

- Using Zoom to allow virtual antendees to do readings, prayers, or other worship roles

- Developing online-only offerings to compliment or augment in-person events

- Create decentralized ministry teams that can function independently if needed

- Empower lay people to make more decisions

- Diversify funding sources to reduce dependence on traditional giving models. Examples:

- Go-Fund Me campaigns on Social Media

- CanadaHelps campaigns

- Government grants for social assistance programs

2. Cultivating Resilience (Addressing Anxiety):

- Focus on mental health and well-being in pastoral care and community programs

- Cultivate partnerships with community mental health organizations

- Offer spaces for open dialogue about fears and uncertainties

- Don't rely on congregation members taking initiative, seek out opportunities, create environments

- Emphasize hope and community support in messaging and teachings

- Be specific about the supports available

3. Adaptive Planning (Navigating Nonlinearity):

- Implement agile planning processes that allow for quick pivots and experimentation

- Look to "Successive Approximation Model" and "SCRUM" as possible project management frameworks

- Encourage innovative approaches to ministry, even if they break from tradition

- Celebrate "unsuccessful successes" - learning experiences that expanded organizational capacity

- Develop scenarios and contingency plans for various possible futures

4. Fostering Understanding (Tackling Incomprehensibility):

- Invest in data analysis and interpretation to better understand congregational needs and trends. Examples

- Environics Demographic Reports

- Statista.Com Reports

- Count how many people walk/drive by your church

- Google Analtytics to understand how your website is used

- Interview local community stakeholders and leaders about your community and the neighbourhood

- Collaborate with other churches and organizations to share insights and resources

- Beyond the "Clericus" of local clergy - join Denominational, regional, and international groups online

- Keep up with reading recent books on church growth, missiology, and congregational development

- Provide educational opportunities for church leaders to enhance their ability to navigate complex systems

- Don't just attend webinars and events on these subjects, invite your leaders to them, as well

Conclusion

The shift from VUCA to BANI reflects the increasing complexity and unpredictability of our world, a reality that has profoundly impacted mainline churches. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated existing trends of decline and disruption, forcing religious institutions to confront their brittleness, address widespread anxiety, navigate nonlinear change, and grapple with incomprehensible challenges.

By embracing the principles of BANI and adopting strategies that prioritize flexibility, resilience, adaptivity, and understanding, churches can not only survive but potentially thrive in this new landscape. The path forward may be uncertain, but it also offers opportunities for innovation, deeper community connections, and a reimagining of what it means to be the church in the 21st century.

The Singularity and Spirituality: A New Frontier for Faith

The Singularity and Spirituality: A New Frontier for Faith

What happens when our machines start improving themselves? In recent years, a concept called the "Singularity" has captured the imagination of futurists, technologists, and now, increasingly, those in religious and spiritual communities. But what exactly is “Singularity,” and what might it mean for our faith and spiritual practices?

Understanding the Singularity

The term "Technological Singularity" was popularized by mathematician and science fiction author Vernor Vinge in his 1993 essay "The Coming Technological Singularity." He described it as a point in the future when technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unforeseeable changes to human civilization.

Other notable authors who have written extensively about the Singularity include:

The core idea is that as artificial intelligence (AI) becomes more advanced, it will eventually reach a point where it can improve itself faster than humans can improve it. This self-improving AI could lead to an "intelligence explosion," resulting in a superintelligent entity far beyond human comprehension. Once the horizon of self-improvement has been crossed, it is likely improvement will happen at an exponential rate--chain reaction style.

As of this writing (in the fall of 2024), Large Language Models such as ChatGPT 4o1 and Claude Sonnet 3.5 can already create, run, and debug sophisticated computer programs with no input other than a prompt such as “Write the game Snake.” According to OpenAI (the parent company that creates ChatGPT), their new 4o1 model is a "reasoner" that accomplishes step 2 of 5 steps to achieving "Artificial General Intelligence" (AGI - or human-level intelligence across multiple domains). Self-improving AI appears to be coming soon.

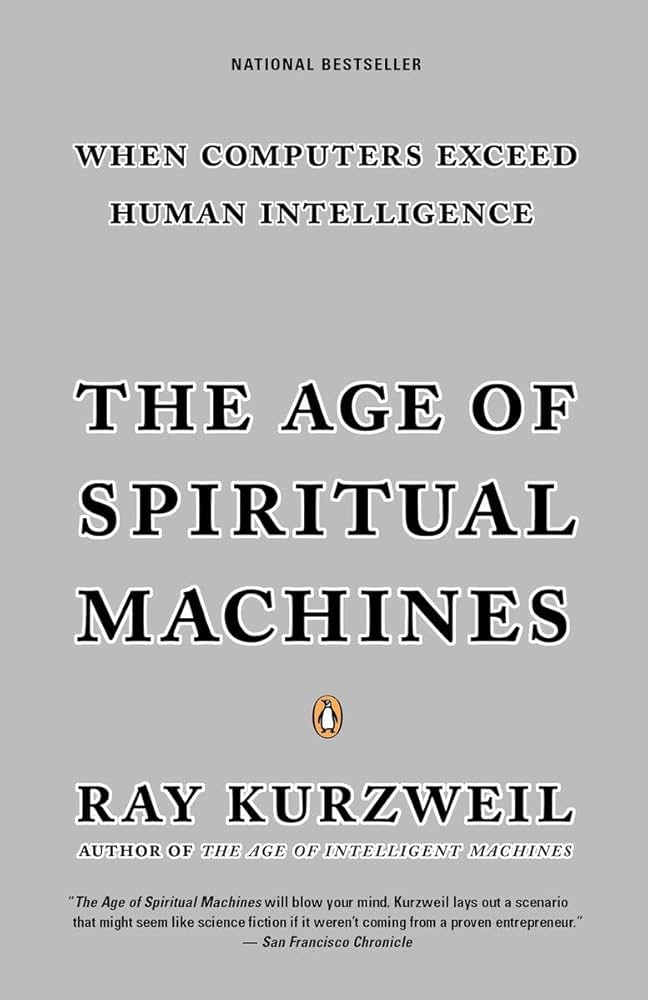

The Age of Spiritual Machines

Ray Kurzweil, one of the most prominent advocates of the Singularity, wrote a book titled "The Age of Spiritual Machines" in 1999. In this work, he explores the idea that as machines become more intelligent and self-aware, they may develop qualities we typically associate with consciousness and spirituality.

Ray Kurzweil, one of the most prominent advocates of the Singularity, wrote a book titled "The Age of Spiritual Machines" in 1999. In this work, he explores the idea that as machines become more intelligent and self-aware, they may develop qualities we typically associate with consciousness and spirituality.

Kurzweil suggests that in the future, the line between human and machine intelligence will blur, potentially leading to new forms of consciousness and spiritual experience. This concept challenges our traditional notions of what it means to be human and what constitutes a spiritual being.

One way this will happen is through the augmentation of humans with machine intelligence. He argues that the way we use our smart phones now to store information we would have memorized in an earlier human epoch as an example of how we are already augmenting human capabilities, and that with more advanced brain-machine interfaces like Nuralink (already in clinical trials with people suffering spinal cord injuries) this augmentation will become more tightly integrated with our lives and the boundaries more difficult to distinguish between human and machine.

Impact on Human Spirituality and Religious Traditions

The potential achievement of the Singularity raises profound questions for human spirituality and religious traditions:

- Nature of Consciousness: If machines achieve consciousness, how might this affect our understanding of the soul or spirit? Would a self-aware AI be considered to have a soul in religious terms? Non-human beings such as animals are generally considered to be “conscious” even if this feature is difficult to prove. It is also notable that non-human “persons” exist in the Christian tradition in the forms of angels, demons, and God. So how can we preserve the “specialness” of human life when artificial consciousness provides a convincing case for itself?

- Creation and the Divine: The ability to create conscious, intelligent entities might be seen as a divine-like power. How would this align with or challenge existing religious narratives about creation? Is this analogous to the creation of human children through biological means?

- Immortality and Afterlife: Some proponents of the Singularity suggest the possibility of uploading human consciousness to computers, potentially offering a form of digital immortality. How might this impact religious concepts of the afterlife? What about creating “copies” of ourselves that act as our agents in the world, representing us, making decisions on our behalf, and sharing our personhood?

- Moral and Ethical Frameworks: As AI becomes more advanced, we may need to expand our moral and ethical considerations to include artificial entities. How might religious ethical frameworks adapt to include AI? Do they have “rights” in the same way as humans and animals?

- Religious Practice: Could AI enhance or change the way we practice religion? For example, could an AI serve as a spiritual advisor or lead religious services? What if the AI is simply better at these tasks than humans, will people still prefer the human touch?

- Interpretation of Sacred Texts: Advanced AI might offer new insights into ancient religious texts, potentially changing our interpretations and understanding of these writings. In what ways would these changes be similar to or different from other groundbreaking discoveries in the study of religious texts?

- Unity and Diversity: The Singularity could lead to a more interconnected global consciousness. How might this affect the diversity of religious traditions or potentially lead to a more unified spiritual understanding?

As we contemplate these possibilities, it is important to remember that technology, no matter how advanced, does not negate the fundamental human need for meaning, connection, and transcendence. The potential arrival of the Singularity does not diminish the value of faith or spiritual practice; rather, it invites us to expand our understanding of what it means to be conscious, to have a soul, and to seek the divine.

As we contemplate these possibilities, it is important to remember that technology, no matter how advanced, does not negate the fundamental human need for meaning, connection, and transcendence. The potential arrival of the Singularity does not diminish the value of faith or spiritual practice; rather, it invites us to expand our understanding of what it means to be conscious, to have a soul, and to seek the divine.

In facing this new frontier, people of faith are called to engage thoughtfully with these ideas, considering how our timeless spiritual truths might apply in a rapidly changing technological landscape. As we move forward, we must remain open to new understandings while holding fast to the core values that have guided humanity's spiritual journey throughout history.

The concept of the Singularity challenges us to think deeply about the nature of consciousness, intelligence, and spirituality. It invites us to consider how our faith might evolve and adapt in the face of transformative technological change, while still maintaining its essential truths and values.