Tay Moss

Blog entry by Tay Moss

From Waterfall to SAM: A Better Way to Manage Church Projects

Many churches pour heart and soul into planning projects – new ministries, building renovations, tech upgrades – only to hit frustration when reality doesn’t match the plan. If you’ve ever sat on a church committee that spent months crafting a detailed plan (perhaps even dozens of pages long) just to see it fizzle out, you’re not alone.

Many churches pour heart and soul into planning projects – new ministries, building renovations, tech upgrades – only to hit frustration when reality doesn’t match the plan. If you’ve ever sat on a church committee that spent months crafting a detailed plan (perhaps even dozens of pages long) just to see it fizzle out, you’re not alone.

One church leader recalled an “excruciating” 18-month strategic planning process that produced a 60-page plan which was promptly “set aside and ignored” (Is your church fragile or agile? - The Center for Healthy Churches & PneuMatrix). Why does this happen so often? A big reason is that we unknowingly follow a “Waterfall” project management model – a linear, plan-everything-in-advance approach – that simply doesn’t fit the unpredictable, people-centered world of church projects. Furthermore, linear approaches like Waterfall become increasingly ill suited to reality. I've written before about the BANI context in which churches operate: Brittle, Anxious, Non-linear, and Incomprehensible. We need project management strategies that match.

In this article, we’ll explore why the Waterfall method often falls short for churches, and introduce a more flexible, engaging approach called SAM (Successive Approximation Model). Don’t worry if those terms are new to you – we’ll break it all down in plain language. By the end, you’ll see how an iterative, feedback-driven process can lead to better results in everything from a kitchen remodel to a new outreach program, and even how we at CHURCHx use this approach to design our courses.

The “Waterfall” Model: Are Churches Unknowingly Using It?

Let’s start with the Waterfall model. What is it, and why might it describe how many church projects are handled? The Waterfall model is a traditional project management approach that works in sequential phases – much like water flowing over a series of falls, each step must finish completely before the next begins (Waterfalls or Whirlpools: Why Use an Instructional Development Model? : Articles | The Learning Guild). In a Waterfall process, you typically plan everything upfront. For example, a team might spend weeks (or months) gathering requirements and opinions, then draft a complete design or action plan, then move into executing it, and finally deliver the result. Crucially, in classic Waterfall you can’t easily go back to an earlier stage once you’ve moved on. It assumes that by the time you start doing the work, the plan is set in stone.

Let’s start with the Waterfall model. What is it, and why might it describe how many church projects are handled? The Waterfall model is a traditional project management approach that works in sequential phases – much like water flowing over a series of falls, each step must finish completely before the next begins (Waterfalls or Whirlpools: Why Use an Instructional Development Model? : Articles | The Learning Guild). In a Waterfall process, you typically plan everything upfront. For example, a team might spend weeks (or months) gathering requirements and opinions, then draft a complete design or action plan, then move into executing it, and finally deliver the result. Crucially, in classic Waterfall you can’t easily go back to an earlier stage once you’ve moved on. It assumes that by the time you start doing the work, the plan is set in stone.

Sound familiar? Church committees often operate this way by default. We form a team to tackle a project – say, renovating the fellowship hall or launching a new youth program. In many cases, the group might spend a long time in the “planning and design” phase, mapping out every detail in one giant blueprint before any action happens. Only when that comprehensive plan is approved do we start implementing. This “plan then execute” mentality is the essence of Waterfall. A common product of this approach is a complex plan, perhaps organized into a "Gantt Chart" with neatly arranged bars showing where one part of the projects ends and another begins.

The Waterfall method can feel reassuring because it emphasizes upfront clarity and a single, agreed-upon plan. In fact, for very predictable, repeatable tasks, a Waterfall approach can work fine (Agile vs. waterfall project management | Atlassian). Some aspects of church life (like routine maintenance or annual events that hardly change) might fit this style. It allows for Church Boards and others to approve all the changes and costs of projects in advance of any action being taken. However, most meaningful church projects are not so predictable – they involve people’s changing needs, creative ideas, and unforeseen challenges. This is where Waterfall’s weaknesses emerge.

Why Waterfall Planning Often Leads to Problems

The Waterfall model’s rigidity often sets churches up for headaches. Here are a few common problems that arise when using this linear approach in church projects:

- Plans Can Become Outdated Mid-Stream: Waterfall assumes you can nail down all requirements at the start, but in reality “it’s impossible to know everything about a project at the beginning.” As work begins, new information and ideas emerge, and “requirements must shift over time to reflect this new knowledge.” If your plan can’t adapt, you may end up with a result that no longer fits the congregation’s needs (What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?).

- No Room for Feedback Until the End: In a strict Waterfall process, stakeholders (like congregation members or ministry leaders) might not see the product until it’s almost finished. “Because the customer is not involved until late in the project, they may not like what they see… When this happens, the project will go over time and budget” trying to fix things last-minute (What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?). In a church context, this could mean the church board or volunteers only get to react once the project is nearly done – when changes are costly or too late. Little issues that could have been caught early turn into big disappointments.

- Changing Course is Difficult: If circumstances change or someone has a new idea halfway through, a Waterfall plan struggles to accommodate it. On account of its rigid format, Waterfall is “unable to accommodate changing requirements or address problems” that pop up during the project (What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?). It’s like a train stuck on one track – great if it’s the right track, but if not, derailment looms. In church life, we know how quickly things can change: maybe a key volunteer moves away, or new opportunities arise. A rigid plan doesn’t handle that well.

- Schedule Overruns Cascade: Waterfall schedules often look tidy upfront (Phase 1 done by March, Phase 2 by June, etc.), but they are fragile. If one phase is delayed, it causes domino-effect delays in all subsequent phases (What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?). For example, if fundraising (Phase 1) takes longer than expected, everything else pushes out, often leading to missed deadlines and frustration. There’s little flexibility to overlap tasks or adjust on the fly.

- Team Burnout and Buy-in Loss: Remember that 18-month planning ordeal? Long, drawn-out planning without visible progress can exhaust volunteers and drain enthusiasm. By the time you finish planning and move to action, people might have lost interest or trust in the project. Rigid processes can also devolve into bureaucratic exercises – “onerous” efforts that produce documents no one uses (Is your church fragile or agile? - The Center for Healthy Churches & PneuMatrix).

In short, the Waterfall method tends to be high-risk for complex or evolving projects. As one project management source bluntly states, in Waterfall “your one chance to make critical design decisions has come and gone” once you’re in the implementation stage (What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?). If the initial plan was flawed or something changes, you’re stuck. No wonder so many church plans end up collecting dust – by the time they’re done, they’re either not quite right or the world has moved on.

Meet SAM: An Iterative, “Successive Approximation” Approach

So what’s the alternative? One better way to manage projects (in churches and beyond) is to use an iterative approach – meaning you plan and build a project in small, repeating cycles, adjusting as you go, rather than in one big cascade. In the software and business world, this is often called “Agile” project management. “Agile Management is an incremental approach… completed in small sections called iterations. Each iteration... is reviewed and critiqued by the project team, and insights… are used to determine what the next step should be.” (Is your church fragile or agile? - The Center for Healthy Churches & PneuMatrix). In other words, you do a little, check how it’s going, then decide what to do next based on feedback. The main benefit of this approach is “its ability to respond to issues as they arise” – making changes at the right time can “save resources and, ultimately, help deliver a successful project on time and within budget.” (Is your church fragile or agile? - The Center for Healthy Churches & PneuMatrix).

One powerful iterative method – and the one I want to highlight here – is the Successive Approximation Model (SAM). SAM was developed by Dr. Michael Allen, a pioneer in instructional design, as a flexible alternative to the rigid planning of traditional models (SAM - Why is it the Preferred Model for E-learning Development?). The name sounds fancy, but it literally means solving a problem by successively approximating the solution – in plain terms, getting closer to the right outcome through repeated small steps. Michael Allen explains that the title itself conveys the approach: taking small and quick steps instead of giant leaps toward each milestone. You don’t try to craft the perfect solution in one go. Instead, you make a little progress, check and adjust, then make a bit more progress, and so on.

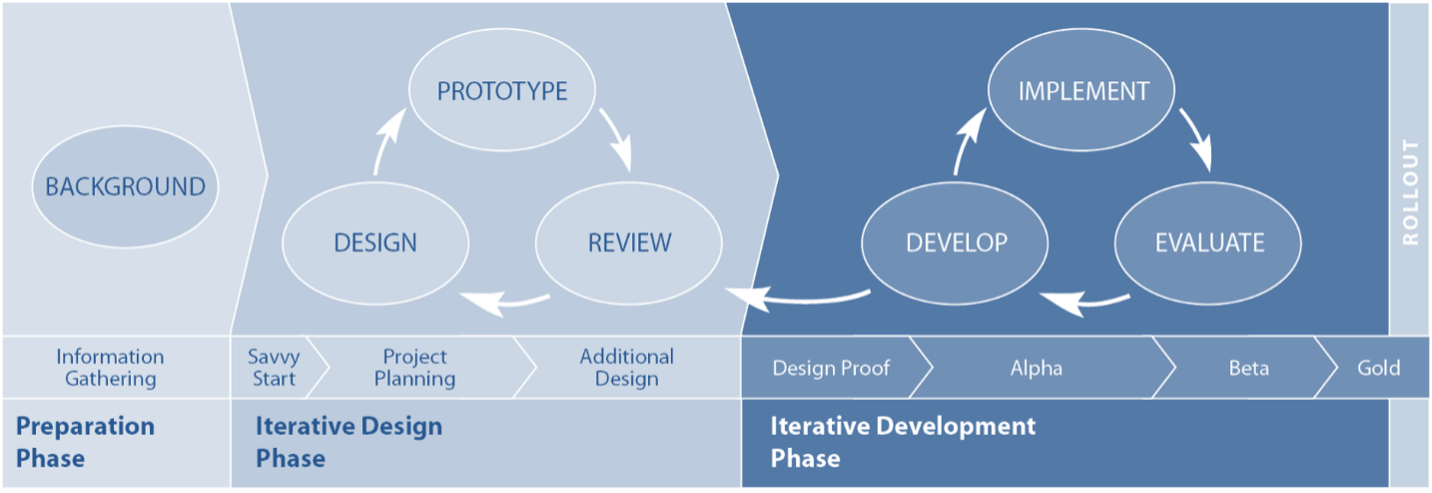

How does SAM work? In practice, SAM breaks a project into three main phases (The Basics of Instructional Design Processes - zipBoard):

- Preparation Phase: Do a quick intake of information and clarify the basic goals and constraints. (In a church project, this is where you’d gather initial input – the wish list, requirements, and any givens like budget limits. Importantly, this phase is kept brief to avoid "analysis paralysis" (The Basics of Instructional Design Processes - zipBoard), because you know you’ll refine as you go.)

- Iterative Design Phase: Hold a kickoff brainstorming session (what Allen calls a “Savvy Start” (The Basics of Instructional Design Processes - zipBoard)) with key stakeholders, then create a prototype or draft of the solution. Crucially, this prototype is not meant to be final – it’s a rough first attempt that stakeholders (users, committee members, etc.) can test-drive and give feedback on. The team then iterates – revising the design and prototype through multiple quick cycles of feedback. The motto here is “fail fast to succeed sooner”: it’s better to catch what doesn’t work early in these sketches or mock-ups than to discover problems after everything’s built.

- Iterative Development Phase: Once the design direction is agreed upon in principle, the project moves into full execution iteratively. The team develops the actual deliverables in small pieces, again cycling through develop → review → improve steps (The Basics of Instructional Design Processes - zipBoard). In Michael Allen’s model for course development, they produce an “Alpha” version (first full draft), get feedback, then a “Beta” version (after fixes), and finally a “Gold” final product (SAM: The rapid fire model of instructional design | by Hannah Young | Medium). The key idea is that even during implementation, you continue to incorporate feedback and make adjustments in stages, rather than delivering the whole thing in one go without checking.

You might be thinking: “This sounds a bit like common sense – work a bit, check in, adjust.” Exactly! It is common sense, but traditional project habits often push us to do the opposite (work a LOT, then check in at the very end). Michael Allen and other experts argue that an iterative model like SAM taps into collaboration and real-world testing to create a better result. Allen notes that a good process “reveals as much about the developing product as early and continuously as possible”, allowing for “frequent evaluation and course correction at times when corrections cost the least.” (Criteria for the Ideal Instructional Design Process Model). In contrast to a linear “plan everything then pray it’s right” approach, an iterative process prevents investing most of the project’s time and budget before stakeholders get to see or shape the product (Criteria for the Ideal Instructional Design Process Model). Small experimental steps can be reversed or modified easily – it’s low-risk to try something early on, whereas it’s high-risk to discover a mistake after full launch.

Another key benefit: stakeholders are involved throughout. SAM “involves the stakeholders throughout the design and development process, and this helps achieve the desired outcomes.” (SAM - Why is it the Preferred Model for E-learning Development?) Instead of a few people going off into a back room to draft the entire plan, you bring in perspectives from board members, volunteers, staff, even end-users (like members of the congregation) at multiple points. This collaborative spirit not only produces a better design; it also increases buy-in. People are more enthusiastic and “on board” with a project they helped shape. The project’s champions aren’t just the committee; it’s everyone who had a voice in the iterations.

Finally, iterative models like SAM introduce a mindset of continuous improvement and learning. Each cycle is an opportunity to learn what works and what doesn’t, and to make the product better. As Allen’s model emphasizes, no project is ever truly perfect – but by cycling through approximations, you ensure it’s as effective as possible within your constraints. You end up with a solution that’s been tested and refined, rather than a first draft masquerading as a final draft.

A Better Way in Action: Using SAM for a Church Kitchen Renovation

Let’s bring this down to earth with a concrete example. Imagine your church is planning to renovate the kitchen in the fellowship hall – a project near and dear to the hearts of the congregation (especially those who cook for potlucks and events!). Traditionally, you might form a kitchen committee, list everything you want, hire a designer to draw up a complete new kitchen layout, present it for approval, then commence construction. That’s a typical Waterfall sequence.

Now, what would it look like to use a SAM-style iterative approach instead? Here’s how the kitchen renovation might unfold with successive approximation:

- Savvy Start – Gather Needs & Brainstorm (Iteration 1): Begin with a collaborative workshop involving all key stakeholders: the property committee, a few frequent kitchen volunteers (the folks who will actually use the kitchen), perhaps a church board representative, and even a caterer or expert if you have one in the congregation. In this kickoff meeting, instead of finalizing a design, you brainstorm and prioritize needs. For example, volunteers might voice frustrations (“The fridge is too far from the prep area” or “We need a second oven”), and together the group identifies what a successful kitchen should enable (faster prep for events, accessible storage, easy cleanup, etc.). With those insights, the team sketches some rough ideas. This could be as simple as drawing different layouts on paper or using tape on the floor of the hall to outline where counters and appliances might go. Nothing is final at this stage – it’s about capturing the vision and key requirements quickly.

- Prototype Design & Feedback (Iteration 2 and 3): Next, take the ideas from the Savvy Start and have a designer (or a skilled volunteer/architect) create a prototype design. This might be a scaled drawing or a 3D digital model of the proposed kitchen. Crucially, share this prototype with stakeholders early. Perhaps call a meeting of the kitchen volunteers and church staff to walk through the proposed design virtually, or even set up cardboard mock-ups of counter heights and appliance positions in the current kitchen to simulate the new flow. Now gather feedback: maybe the volunteers notice that the proposed island would block movement, or the pastor suggests adding a coffee station for coffee-hour time. Because this isn’t a finished construction, changes are relatively easy – move the tape marks, adjust the drawing. Over a couple of quick review and revise cycles, the design is improved. You might go through a few iterations: design v1, feedback, design v2, more feedback... until stakeholders are generally happy. Importantly, even at this stage you haven’t spent much money – just time and perhaps a small design fee – but you’ve caught issues that would have been expensive if discovered during construction.

- Staged Implementation with Continuous Input: With a vetted design in hand, you proceed to implementation, but you still keep it iterative. For instance, if budget and logistics allow, you could renovate in phases rather than shutting down the kitchen entirely. Start with one part – say, installing the new storage cabinets and relocating the pantry. Once that mini-project is done, let the kitchen volunteers start using the new setup and solicit their input: Are the new cabinets helpful? Is anything hard to reach? This is analogous to an “Alpha” release. Use their feedback to make small tweaks (maybe you add an extra shelf or change the kind of handles) before moving to the next phase. Then tackle the cooking area renovation (new stove, island, etc.), again perhaps testing it during a church event before finalizing all the finishing touches (your “Beta” phase and refinements). At each stage, stakeholders get to interact with the evolving project and you, as the project lead, can adjust course. By the end, you’ll have a “Gold” version of the kitchen that has been shaped by its users. The result is likely a kitchen that truly meets the congregation’s needs, with far fewer “I wish we had known…” regrets.

Throughout this process, communication is constant. Church board members get regular updates and see progress, which builds confidence. The congregation hears about the improvements in stages, generating excitement (“We’ve installed half the new appliances – come take a look and tell us what you think after Sunday’s potluck!”). Any problems that arise (maybe the flooring ordered for phase 2 was discontinued – oops!) can be dealt with by adjusting the plan for phase 3, rather than derailing the entire project. And because you didn’t try to perfect the plan upfront, the team stays energized focusing on solving the next set of issues rather than lamenting that the original plan isn’t working. Consider putting weekly updates (perhaps pictures?) in the Sunday bulletins on emails sent to the congregation list.

Bottom line: By approximating the final kitchen through successive iterations – listening, prototyping, refining, and implementing in pieces – the church ends up with a better kitchen and a happier team. The project stays more on schedule and on budget because you caught missteps early and adapted (no costly change orders at the 90% mark!). And those who use the kitchen feel ownership because they were involved from the beginning.

Other Church Projects Ripe for an Iterative Approach

The kitchen example is just one scenario. Nearly any church project that has some level of uncertainty or creative design can benefit from SAM’s iterative, feedback-driven philosophy. Here are a few other examples:

- Church Website Redesign: Instead of hiring a web designer to build the entire site and launching it in one big reveal (only to find the congregation finds it confusing), use iterative design. Create a prototype or demo site with just a couple of pages, have staff and members test it and give feedback on the navigation and content. Improve it in cycles. Maybe run a beta version of the site for a small group to gather feedback before full launch. By involving end-users (members, seekers, etc.) during development, you ensure the final website is user-friendly and effective.

- Launching a New Community Program: Say your church wants to start an after-school program for kids. Rather than planning the full program for six months and rolling it out lock-stock, consider launching a pilot program first. Run it for a shorter period or with a smaller group of kids, then gather input from parents, volunteers, and the kids themselves. What activities did they enjoy? Where did logistics fall short? Use that feedback to expand or adjust the program before committing all your resources. This successive approximation can turn a good idea into a truly impactful ministry by refining it with real-world data.

- Sanctuary Renovations or Reconfigurations: Perhaps you’re considering a big change in the sanctuary (new seating arrangement, lighting, or sound system). The Waterfall way would be to decide everything (maybe by one committee) and implement over a few weeks of construction. A SAM-inspired way could be testing changes in small ways. For example, before replacing all your pews with chairs, try removing a few pews at the back and setting up sample chairs for a month to see how it affects worship and get congregational feedback. If considering new lighting, install it in one section and gather reactions. These iterations can prevent costly aesthetic or functional mistakes and help build consensus. People can experience the changes gradually and offer input, leading to a final renovation that’s well-received.

In each of these cases, the pattern is to start small, involve the stakeholders, and iterate. You’re essentially de-risking the project – no single decision or design is beyond revising, so you rarely get stuck with a “failure” at the end. Problems are caught early when they’re easier (and cheaper) to fix, and the final outcome better matches what people actually need and want.

How CHURCHx Uses SAM for Better Courses

At CHURCHx, we believe in practicing what we preach. Interestingly, the Successive Approximation Model isn’t only useful for tangible projects like buildings and websites – it’s also great for designing educational experiences. In fact, SAM was born in the world of instructional design. We use SAM’s iterative, feedback-driven approach to create our church courses and training programs, and we’ve seen firsthand how it leads to better learning outcomes.

What does this look like? Let’s say we’re developing a new online course for small group leaders. Instead of writing all the lesson content, filming all the videos, and uploading a finished 8-week course before anyone outside our team sees it (which would be the Waterfall way), we take a SAM approach:

- Early Prototyping: We might start by conducting a “Savvy Start” workshop with a few experienced small group leaders and some people from our target audience. In this collaborative session, we gather insights on what challenges small group leaders face and what they’d love to learn. Based on that, our team rapidly drafts a prototype of one module – perhaps an outline of a lesson or a sample video segment. This is our course prototype.

- Feedback Cycles: We then share this prototype with the stakeholders for feedback immediately. Those volunteer leaders might say, “This example isn’t realistic” or “We actually need more help with facilitating discussions than with choosing materials.” We listen and adjust. Maybe we create a quick beta version of one lesson – with a short interactive activity – and have a few people test it (almost like a focus group of learners). Their input at this stage is gold. We incorporate their suggestions and iterate the design of the course before building the whole thing. As Michael Allen often points out, a functional prototype that learners can “test drive” is the best way to spot design flaws early, and we find that to be true. It’s much better to find out in week 1 that a quiz format is confusing than to only learn about it after the entire course is live!

- Alpha and Beta Releases: Once we’re happy with the direction of one module, we develop the Alpha version of the full course – all modules created, but not yet finalized. We might pilot this Alpha course with a small group from one partner church. During this pilot run, we actively solicit feedback: which lessons resonated most? Where did learners get stuck? What did they find boring or incredibly useful? Using that data, we go back and refine to a Beta version. Perhaps we trim a section that dragged on, add more examples to a weak lesson, or re-record a video to be more engaging. By the time we release the final “Gold” version of the course to all churches, we’ve run through multiple cycles of improvement.

The result? A training course that we know (through testing) is engaging, clear, and effective for our audience. This iterative design not only helps us build a better product, but it also saves resources in the long run – we’re far less likely to need a major overhaul or to receive lots of support requests later, because we ironed out the kinks through successive approximations. As one summary of Michael Allen’s approach put it, such iterative processes simplify development and yield more energetic and effective learning experiences (Leaving ADDIE for SAM: An Agile Model for Developing the Best Learning Experiences | Welcome to TeachOnline). We’ve found that to be true: by involving real users (church leaders, congregants, subject matter experts) at each stage of course creation, our end programs are more relevant and impactful.

Perhaps just as important, SAM keeps us aligned with the needs of those we serve. It’s easy for any creator to make assumptions about what people need. Iterative feedback is a built-in humility check – it forces us to listen continuously. In a church context, this is invaluable. Our courses aren’t developed in an ivory tower; they’re co-created with input from the community. That means when you take a CHURCHx course, you’re benefiting from the collective wisdom of many, not just the initial ideas of a few.

Moving Forward: Learning to “Think SAM”

Shifting from a Waterfall mindset to an iterative SAM mindset may feel like a big change, but it’s truly about embracing flexibility and feedback. Start small: on your next project, intentionally plan for a prototype or trial run. Invite stakeholders into the process early on – even if it’s a bit messy – and be willing to adjust. Build time for multiple drafts rather than expecting to get it perfect in one draft. You’ll likely find that this approach not only leads to a better end result, but makes the journey more collaborative and less stressful.

Churches, at their heart, are communities of people. And people change, learn, and grow as they engage with a project – they’re not static requirements. By using SAM or any iterative approach, you allow the project to grow with the people involved. It turns project management from a strict script into a responsive dialogue. As Agile project management experts would say, it values “responding to change over following a plan” (Is your church fragile or agile? - The Center for Healthy Churches & PneuMatrix) – a principle that resonates deeply in ministry, where responsiveness can mean the difference between a missed opportunity and a Spirit-led success.

Many churches have been unintentionally using a Waterfall approach, planning every detail and then executing, only to face frustration when reality intervenes. By recognizing this and pivoting to a Successive Approximation Model, we can steward our projects more faithfully and effectively. Small steps, continuous feedback, and iterative improvement can transform not just our outcomes, but also the experience of working together on a project. Whether it’s a building project, a new ministry, or developing learning resources, let’s “think SAM” and invite a process that is adaptive, collaborative, and ultimately more rewarding for everyone involved.

Further Reading

To explore these ideas further, here are some accessible resources on project management and SAM for non-experts:

- “Is your church fragile or agile?” – Bill Wilson (Center for Healthy Churches): A thoughtful blog post on how agile planning principles can benefit congregations (Is your church fragile or agile? - The Center for Healthy Churches & PneuMatrix) (Is your church fragile or agile? - The Center for Healthy Churches & PneuMatrix). Great for seeing Agile ideas applied in a church context.

- “SAM – Why is it the Preferred Model for E-learning Development?” – CommLab India: An easy-to-read introduction to the Successive Approximation Model, including what it is, why it was developed by Michael Allen, and its advantages (SAM - Why is it the Preferred Model for E-learning Development?) (SAM - Why is it the Preferred Model for E-learning Development?). Though focused on e-learning, the concepts are very transferable to other projects.

- “ADDIE Model vs SAM Model: Which is Best for Your Next eLearning Project?” – eLearning Industry: A comparison of the traditional linear ADDIE process and the iterative SAM approach (SAM Model Versus ADDIE Model - eLearning Industry). Helps to illustrate the differences between waterfall-like and agile-like methods in plain language.

- Leaving ADDIE for SAM by Michael Allen (Book Summary – TeachOnline.ca): A brief overview of Michael W. Allen’s book Leaving ADDIE for SAM, explaining why the old linear models were updated and how SAM incorporates more creativity and stakeholder input (Leaving ADDIE for SAM: An Agile Model for Developing the Best Learning Experiences | Welcome to TeachOnline). Useful for those who want the theoretical background from the expert himself.

- “What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?” – PM Column: An article that lays out the pitfalls of Waterfall project management in simple terms (What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?) (What is the Downside of Using the Traditional Waterfall Approach?). Reading this can reinforce why an iterative mindset is beneficial, by seeing what to avoid.